Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) has been called the modern road, the electric pipes, the operating system of the country, and the launch pad of digital economies and governments. Pick your brick and mortar metaphor, the point is to make the critical connective tissue and back-office functions of the digital realm visible, to emphasize both the public and infrastructure parts of the acronym, evoking past eras of public investment in, and public benefit from, the central assets necessary to operate a city, a country, a household, or a business.

The term gained prominence in the early COVID-19 pandemic, as governments around the world scrambled to operate through in-person service and work closures. But the concept comes from some of the world’s leading and most dynamic digital governments who have been advancing other nations long before 2020 (e.g., Brazil, Estonia, Kenya, and India).

The World Bank reports that countries with existing digital payment systems were able to reach 3 times as many recipients with emergency cash transfers, to cushion the economic shock of whole sectors pausing and maintain access to the everyday systems people rely on. “Countries with good DPI in place could also keep government services, commerce, hospitals, schools, and other operations functioning through online channels” (World Bank, Digital Progress and Trends Report, 2023).

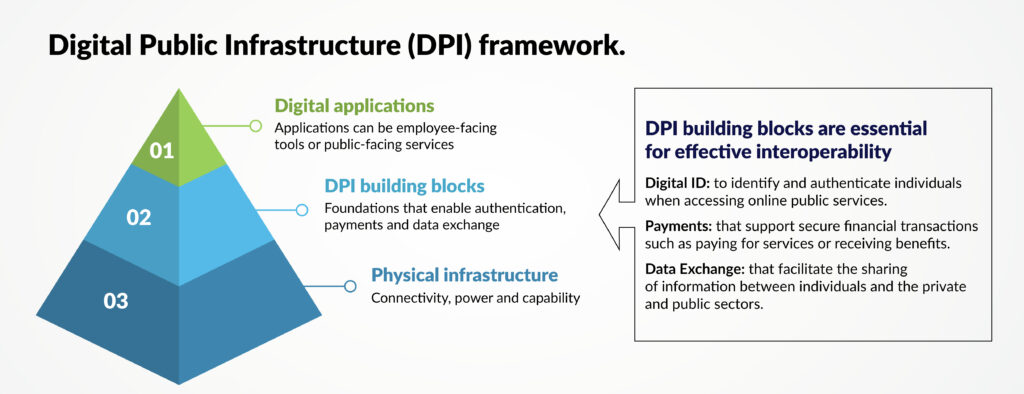

Metaphors aside, a better way to think about DPI is as the “intermediate layer” in a digital ecosystem sandwich, sitting on top of the physical structures (e.g., internet cables, computers, smart phones, data centres, cloud servers, routers, and modems), and enabling software applications across numerous verticals (e.g., e-commerce, social services, remote education, and telehealth), without needing to build separate systems for every service provider or government department.

The international consensus

The 2023 G-20 multilateral consensus and guiding principles on DPI recognized both a universal set of open standard building blocks and international flexibility in implementation, architecture, and levels of centralization and user-centricity.

At the core, they agreed that national DPI requires:

- Digital identity systems: secure records and digital confirmation of identity, which allows access to banking, government benefits, and other services.

Example: a driver’s license stored in a digital wallet and the digital systems needed to confirm that it is valid and share it with verifiers, such as car rental companies. - Digital payment systems: instant transfer and receipt of money from government-to-person, similar to modern banking’s e-transfer systems, but accessible without a bank account.

Example: Pix in Brazil is a 24/7 transfer system operated by the Central Bank of Brazil, using QR codes, Pix keys, or traditional banking details. - Data exchange systems: secure and interoperable information flow systems, including physical and digital infrastructure and the enabling legal and policy frameworks, between both public sector and private sector organizations.

Example: Estonia’s x-Road is an open-source, centrally-managed, distributed Data Exchange Layer (DXL), described by the Estonian government as the “backbone of e-Estonia”.

Caption: Pyramid with 3 levels showing the Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) framework.

Level 1 (top) is digital applications: applications can be employee-facing tools or public-facing services. Level 2 (middle) is DPI building blocks: foundations that enable authentications, payments, and data exchange. Level 3 (bottom) is physical infrastructure: connectivity, power, and capability. DPI building blocks are essential for effective interoperability. Digital ID: to identify and authenticate individuals when accessing online public services. Payments: that support secure financial transactions such as paying for services or receiving benefits. Data exchange: that facilitate the sharing of information between individuals and the private and public sectors.

When built well, and well-funded, DPI can have significant real-world payoffs. It could make life easier for citizens every time they interact with the government, be good for the economy, and make our communities more inclusive.

Here are some of the big reasons DPI matters:

- Enables a better, modern user experience.

- Improves inclusion and equity through digital-first, not digital-only services, accessible even in remote locations.

- Reduces the cost of duplicate systems and duplicate information shared and stored in government systems.

- Enables economic growth through enabling infrastructure that the private sector can build on, while reducing rent extraction for critical functions.

- Improves trust in government institutions.

The Canadian context

A more digitally-mature government will improve economic resilience and help Canadian businesses grow. Investing in digital trade infrastructure will simplify cross-border transactions and allow small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to scale more easily in global markets. Strengthening digital service delivery will create a more predictable, transparent, and efficient regulatory environment, allowing businesses to focus on growth rather than administrative burdens.

As a signatory of the G20 Leaders’ Declaration, Canada recognizes “that safe, secure, trusted, accountable and inclusive DPI, respectful of human rights, personal data, privacy and intellectual property rights can foster resilience, and enable service delivery and innovation”. But our progress has been uneven, and we still rely heavily on international vendors, including cloud providers, and lack data sovereignty over our own residents’ data. We have made a serious step forward with the publication and implementation of the GC Digital Ambition, the 2023–2026 Data Strategy for the Federal Public Service, and the GC Cloud Strategy, to name a few. We have world-class talent in place, but Canada has some catching up to do.

Founded in 2017, the Canadian Digital Service’s mandate is to enhance whole-of-government service delivery, building self-serve platform products, offering digital expertise, and improving the public’s experience on Canada.ca to find information and complete tasks. Our early focus was on the top layer of software the public interacts with when applying to, and receiving notification about, government programs and services.

Today, we are one third of the way to building the UN endorsed three core DPI requirements. Alongside scaling our existing products, we are developing a unified approach to digital identity called GC Sign in: a secure, inclusive, and user-friendly platform that allows individuals to have one sign in method to access Government of Canada services. We are also building a product called GC Issue and Verify, which will give government departments the ability to issue digital versions of the physical credentials they already provide, like work permits and boating licenses.

From our vantage point in Service Canada, we see the problems that these missing infrastructure gaps pose to service delivery. As policy advisors in a delivery organization, we look first to ensure we have the enabling frameworks that provide authorities, smooth collaboration, and unlock implementation.

What are we proposing?

- Review and update Canada’s major policies to provide the necessary scaffolding for the infrastructure view of the government and ensure that enabling conditions are met. This includes the Policy on Service and Digital, Policy on Government Security, Policy on the Planning and Management of Investments, the Privacy Act, and Access to Information Act. This renewal work is both critical and, by necessity, iterative, needing to adapt to ever-changing best practices and digital technology.

- Make critical decisions on prioritizing enterprise investments. We need to be smarter and bolder about financial allocations, even if that means there will be winners and losers in the system, and ensure that not all our funding is locked up in large-scale and under-performing investments while mission-critical work is stuck in the queue. Otherwise, we risk making empty commitments that the system cannot implement and we cannot afford.

- Make long-term commitments to the remaining missing core infrastructure. Building infrastructure requires predictable, long-term funding and stable hiring, ensuring institutional knowledge transfer isn’t disrupted by high-turnover, and energy and resources often spent chasing project-specific pilot funding can be better used. The public needs to know we can meet our timelines and teams need to have the certainty that they can take the project across the finish line. DPI is meant to be an integrated system, and we cannot reap the full benefits of our investments, in service improvements, savings, or economic development, without meeting the G20 consensus on core infrastructure.

Where do we go from here?

Digital transformation is a bit like a major home renovation. You need a plan, the right experts, and a willingness to open up some walls. It won’t happen overnight or by flipping a single switch. But with sustained effort, organizational alignment, coordination, and discipline, we can get it done!

First, we need a federal DPI Strategy, a vision that identifies the core building blocks Canada needs to ensure coordination across the system. Delivering the strategy will require all GC Digital ecosystem players to work together in lock-step, with proper accountabilities and enabling conditions in place.

- TBS and the Office of the Chief Information Officer of Canada (OCIO) are the policy lead. They will continue to set direction and the enabling conditions required for success, creating clarity around accountabilities and roles and responsibilities, and ensure sufficient funding, prioritization of efforts, transparency, and accountability. They are committed to conducting evergreen reviews of policies and directives and providing a unified evaluation framework to ensure DPI performance data can indeed be evaluated GC-wide.

- Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSE) colleagues are the security lead, playing a crucial function in protecting the Canadian government’s electronic information and communication networks.

- Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) is the government transformation and procurement lead for the GC. PSPC should play a key role in steering digital transformation toward public good. Shared Services Canada (SSC), under the Government transformation portfolio, is the infrastructure lead, playing a key role in managing IT infrastructure services, ensuring that effective and efficient business management processes happen, fostering innovation in digital technology and enabling government transformation. As the IT infrastructure and technology provider, SSC plays an important role, in collaboration with TBS OCIO, on architecture and policy.

- Service-focused delivery departments such as Employment Social Development Canada (ESDC), Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), and the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) serve as the interface with the public and the access point to the improved programs and services that DPI enables. These organizations are instrumental in preparing the way for adoption, and ensuring the results lead to improved services for the public.

Finally, this work can’t happen in a vacuum. In Canada, there are many bodies already working to ensure alignment on a broad direction for DPI beyond the federal sphere, with not-for-profit groups, such as the Institute for Citizen-Centred Service (ICCS) providing organizational coordination. This includes the Public Service Chief Information Officer Council (PSCIOC), the Public Sector Service Delivery Council, the Joint Councils, the Digital Governance Council, and various senior management tables.

Internationally, this work must be in dialogue and continued relationship with the private sector, academia, and other community partners. Already the University College London’s Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose has launched a Community of Practice and mapping exercise on DPI Measurement to coordinate common measurement tools to investigate DPI impact.

Not a silver bullet, but a BIG opportunity

Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) is not a silver bullet for modernizing government or addressing service backlogs and public frustration. We still need to do the work of designing with users, and ensuring that the programs and services that digital infrastructure connects are sound. But it is, as its name suggests, necessary public infrastructure.

At CDS, we have already seen mindsets shifting within government, with more talk of shared platforms instead of a multitude of individual departmental solutions. We have been part of small successes, and we’re gearing up for bigger ones. The work starts now, and we at the Canadian Digital Service are excited to help lead the way. Together, we can build a more connected, efficient, and accessible digital future for Canada.

Stay up to date on the latest DPI developments by signing up for our newsletter and following us on LinkedIn.