Writing privacy notices that are easy to read and understand

Privacy notices and website privacy policies can be long documents with confusing language that often never get read. But what if they were shorter – let’s say 80% shorter? And what if they still met legal and policy requirements and provided users with the information they needed in plain language? With the help of our content designers, as well as privacy and legal colleagues, we’re making this a reality in the products we build.

In June 2020, the Canadian Digital Service (CDS) was asked to work with Health Canada to develop and launch an exposure notification service to help limit the spread of COVID-19. Public trust was a foundational priority for COVID Alert: widespread adoption of the app depended on it, and protecting users’ privacy was a critical part of maintaining this trust. Doing this effectively required a robust and publicly-visible technology implementation, and an ability to clearly communicate to users what information could be collected and shared by the app. One tool to help achieve this is privacy notices.

It takes a village

Alongside easy-to-understand content throughout the app, we wanted to make sure that COVID Alert’s privacy notice was also easy to read and understand. Traditionally, privacy notices for government services have been full of jargon and legal terminology. Like the privacy terms for popular consumer products on the web, you might just skip through without reading them, missing key information on how your personal information will be handled. We wanted to do better.

We turned to content design practices and the legal design field, to help make the COVID Alert privacy notice more accessible to people. Using language and design to inform people of their legal rights in ways that they can understand originated in the access to justice field; you can read more about it in this Access to Justice in Canada report (section 11.3) or this article on the plain language movement and modern legal drafting (pages 20-21).

Writing COVID Alert’s privacy notice was a collaboration among CDS’s content designers, policy advisors, and Health Canada’s Privacy Management Division. We iterated on it quickly over the course of a few weeks, since the privacy notice had to be in place for the launch of the app.

Health Canada’s privacy team provided a lot of thoughtful expertise as the notice was developed, and collaborated with CDS on an in-depth privacy assessment of the overall COVID Alert service. They also engaged with stakeholders and technical experts from the Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC), who provided feedback and recommendations to improve the notice.

One of the OPC’s key recommendations was around the use of the word “anonymous”, which we had used in earlier drafts of the privacy notice. As we wrote in a 2020 blog post:

Part of the OPC’s feedback on initial versions of the app was that we used the word “anonymous” to describe how the app works and what information it collects. “Anonymous” implies that there is no risk whatsoever that a person could be identified, however, and although we all agreed that while there’s a very, very low risk that someone could be re-identified through the app, it isn’t necessarily zero. Someone living in a remote area and only interacting with one or two other people could theoretically be identified by their neighbours if they received exposure notification alerts, for example.

This change was an example of bridging the gap between precise terminology (often with legal or policy implications) and language that’s clear and easy to understand. “Anonymous” could fall into either category, depending on who you’re speaking to. For legal and privacy experts, “anonymous” has precise meanings such as “impossible to connect to an individual”. For others, it’s a stand-in for the concept of protecting privacy. In our case, we wanted to communicate that people’s privacy was protected, using technology approaches that made it very, very unlikely but not impossible for them to be identified.

As we iterated on the privacy notice, we appreciated that Health Canada’s privacy team supported our content designer on most elements of wording and structure (outside of precise terminology such as “anonymous”). That can be rare in legal or legal-adjacent fields (like privacy) and ultimately it made a big difference in achieving a privacy notice that met legal and policy requirements while still being easy to read and understand.

Communicating privacy in the context of services you’re building

Doing this in practice can sometimes be a tricky balance; we want to provide people the information needed to meaningfully consent to using an optional service, but a lengthy notice that is full of jargon may be intimidating or difficult to understand. How can we help people inform themselves, without scaring or boring them into skipping over the notice?

Being transparent about what the government is doing with personal information and data also involves thinking about it outside of just privacy notices and assessments. For example, instead of limiting the information to a dedicated page, we can give “notice” of privacy details and privacy protections throughout someone’s experience using an app or online service (including the welcome screen, or when people undertake a particular action, such as submitting a form).

COVID Alert was a fairly unique case, compared to many government services, in that it did not collect personally-identifying information. In some ways that made it slightly easier to write the app’s privacy notice, but it made it even more important to clearly explain how the app (and underlying technologies) worked.

A stepping stone to simpler privacy notices everywhere

Over the past year, we’ve refined other CDS privacy notices. They meet Privacy Act and Treasury Board policy requirements; they provide details on authority to collect, what information is collected and why, how it is handled, and whom to contact with any concerns or how to make a formal complaint. They’re also much, much shorter than the privacy notices that they replaced, communicating what they need to in less verbose, less complex language.

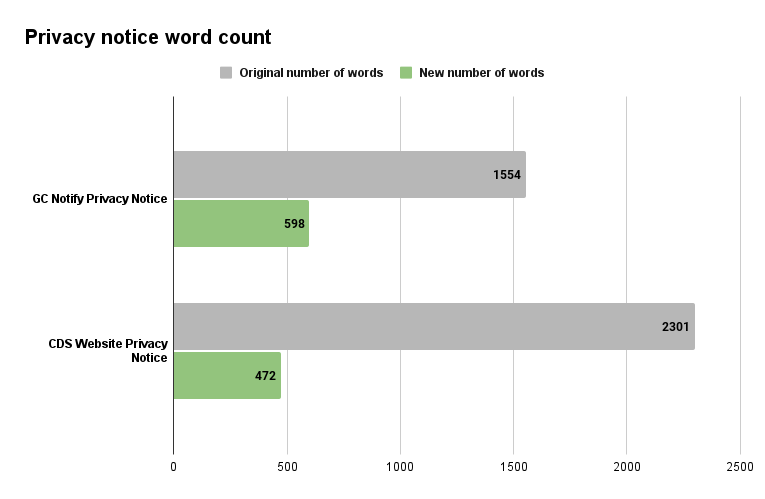

For example, the previous version of the GC Notify privacy notice was 1,554 words. The new GC Notify version is 598 words (2/5ths the original length). The old CDS website privacy notice was actually three different notices totalling 2,301 words. The new CDS website version is 472 words (1/5th the original length) with all the information in one central place.

Alt text: “A chart titled “Privacy notice word count” with horizontal bars indicating the number of words in two different CDS products (GC Notify and the CDS website). For each, a longer grey bar indicates the original number of words, while a shorter light-green bar indicates the new number of words. Each green bar is about 20 or 30% the length of the associated grey bar, showing how the new versions are much shorter in length.”

We’ve already received positive feedback from GC Notify clients on the readability of the new privacy notice, just a few weeks since launching it:

“I am an IT Security Risk Management practitioner and I think that the GC Notify Privacy and Security statements are well written. I love the fact that they are clearly stated on the website.”

We’re really grateful to our privacy colleagues in the Office of the CIO and TBS’s Strategic Communications and Ministerial Affairs divisions, who helped us iterate and improve on these. We’re also grateful to the thousands of people who helped beta test COVID Alert before it launched, and provided feedback on the privacy notice and other app content.

We hope these privacy notices can serve as a useful example for teams improving digital services and websites across government. Making privacy notices that people can easily read helps them better understand how their information is being used, what legal rights they have, and how to get in touch if they have concerns. It’s empowering and it builds public trust in the services you’re working on.